The City has before it a once-in-a lifetime urban planning opportunity to address the need for office space, residential density, and retail on the city-owned parcel known as “The Trop.” But more importantly it has an opportunity to redevelop in a way that acknowledges a dark time in the City’s past and, perhaps in some small way, heals an injustice. This 86 acre plot isn’t just prime real estate, it’s a once-in-a-lifetime chance for a do-over.

The process of deciding the Trop’s future is now coming to a head. Mayor Ken Welch is expected to announce a decision on a development company in the next few weeks. Mayor Welch is the city’s first African-American Mayor, a former resident of the Black neighborhood that once thrived on the site, and the son of a former City Council member who was involved in some of the City’s formative decisions on the area. St. Petersburg’s new mayor will now play a pivotal role in deciding the future of a location fraught with discord.

ADVERTISEMENT

Understanding the complex history of the Trop Site

No one involved in the site’s redevelopment will deny that we must honor the area’s past. But what exactly do they mean? It’s a complicated history, and often unpleasant.

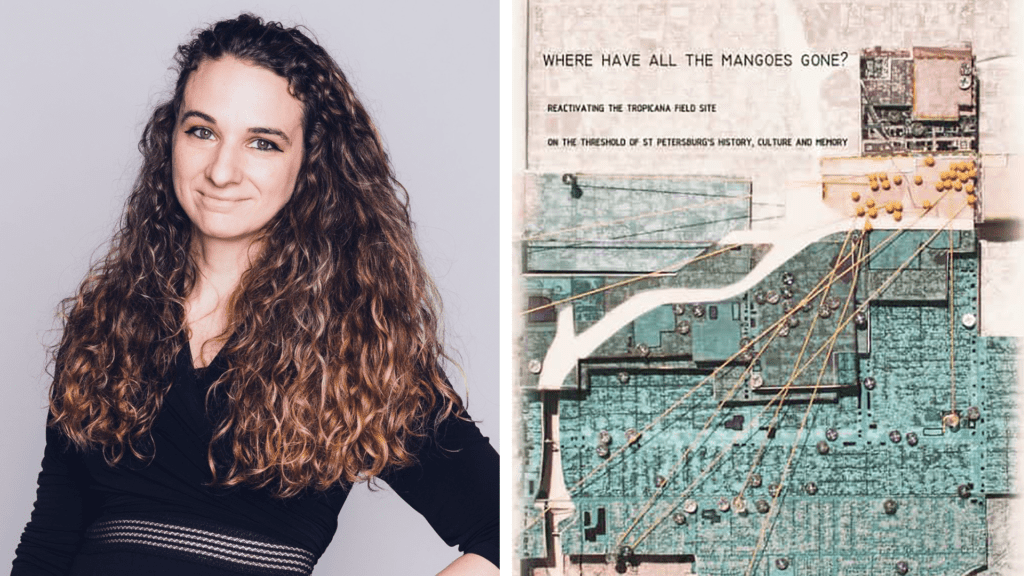

To help me understand both the past and the potential future of the Tropicana site, I sat down with architect Sarah-Jane Vatelot, team member of Sugar Hill Community Partners, one of the two developers vying for the chance to redevelop the Trop. She has studied the area’s history extensively and is thoughtful about its future.

Sarah-Jane was just 13 when she moved to St. Petersburg from France. It wasn’t until some twenty years later as a student working on a Masters degree in architecture at USF, that she participated in a design charrette on the future of Tropicana Field and realized that there was controversy to the history of the site. “Like many people that move here from somewhere else, I didn’t know what questions to ask or even that there were questions to ask about why Tropicana Field was there, what was there before it, and why it’s a problem now.”

The charette sparked a desire to know more, and she spent the next eight months on a “journey to understand why some people view Tropicana as a site to develop and others have much deeper, more painful memories associated with it.”

Traveling back to the birth of St. Pete in 1888

Her work culminated in a Master’s Thesis which has since been published in book form by the St. Petersburg Press. Where Have All the Mangoes Gone: Reactivating the Tropicana Field Site on the Threshold of St. Petersburg’s History, Culture, and Memory. The work garnered the attention of city leaders, developers, and residents that heretofore may not have fully grasped the nuances of the Tropicana site’s history.

So what exactly is the problem? To understand, we have to go back; back to the years just before the city was officially founded in 1888.

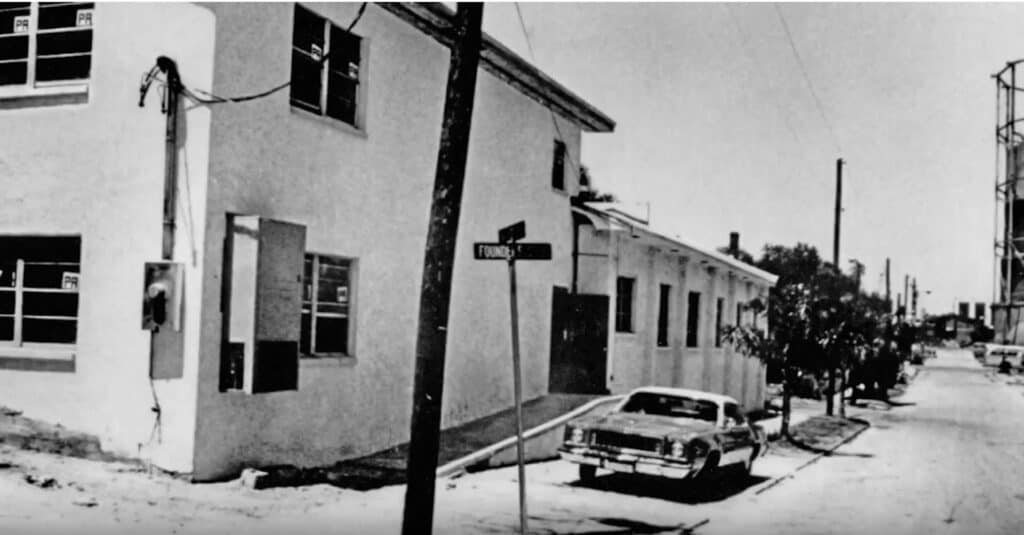

Sarah-Jane summarized some of that history for me: “The people who built St. Petersburg were the African-American rail workers who built the Orange Belt Railroad. They settled in three neighborhoods. The first one was Peppertown, east of where Tropicana Field is currently located. You still see some of the neighborhood’s old courts, although they are quickly going away. After that came Cooper’s Quarters, which was on the northeast corner of today’s Tropicana Field, and grew from there.”

Coopers Quarters, along with numerous other “micro-neighborhoods” like Little Egypt and Forty Quarters, eventually came to be known collectively as the Gas Plant neighborhood, named after two large city-owned gas storage cylinders in the neighborhood.

A third Black neighborhood, Methodist Town, was the only neighborhood located north of Central Avenue.

Drafting “security maps” in St. Pete after the Depression

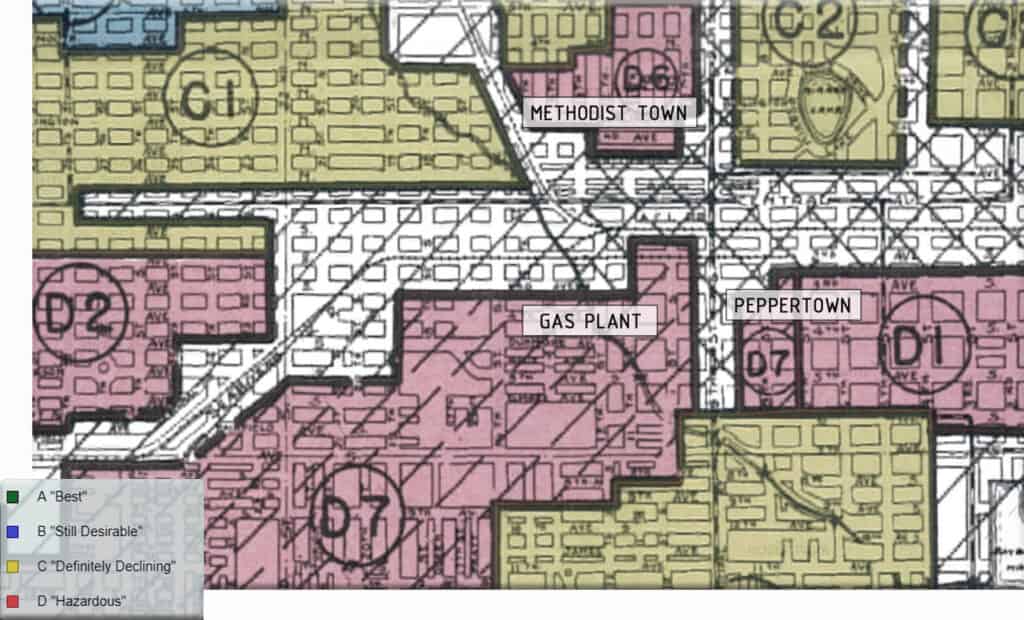

Sarah-Jane points out that, while it was understood by custom that Black residents would live in one of these three neighborhoods, “segregation wasn’t ‘official’, it was sort of an unspoken thing, that people would group together for safety.”

That all changed following the stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression. As part of efforts to devise strategies for economic recovery, the federally funded Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) began drafting “Security Maps” which designated certain areas of cities as “hazardous” or “declining’ and not worthy of investment. These maps had devastating consequences for economically disadvantaged communities across the country, and their negative uses eventually came to be known as “redlining.”

Sarah-Jane reveals “we can see a direct link between those maps, which identify as ‘hazardous’ the three historically African-American neighborhoods of Peppertown, the Gas Plant, and Methodist Town, and the 1935 negro segregation maps in St. Petersburg.”

She’s referring to the city’s 1935 “Negro Segregation Project”; an effort to relocate all of the city’s black residents to areas away from the tourist-oriented downtown. A relocation zone just ten blocks long by 18 blocks wide was proposed, roughly located between 5th Ave South and 15th Ave South and 34th Street on the West to 16th street on the east.

Plans cloaked as “urban renewal”

“When you look at the disappearance of those historic neighborhoods one by one, we can see a direct link to those maps.” Sarah-Jane points out. “By the 1940s Peppertown was essentially gone. They had called the area blighted and relocated people that lived there to Jordan Park.” Newly built by the Housing Authority on land that was donated by the prominent African-American businessman Elder Jordan, Jordan Park enabled people to get on their feet. Sarah-Jane notes: “It was a great success story, but it also effectively heralded the disappearance of Peppertown.”

Later, in the 1970s and 1980s, federal dollars provided means by which the city could once again flex its muscle. Officially sanctioned segregation was out, but similar efforts cloaked as “urban renewal” were in.

Long past its heyday as one of America’s most popular tourist destinations, St. Petersburg was desperate to revitalize its image. It could now use federal money to reshape the city in a way it believed would appeal to visitors.

Efforts focused first on the only historically African- American neighborhood north of Central Avenue, Methodist Town. Long decried in local newspapers as a den of crime (often in blatantly racist language that is shocking to a modern reader) city leaders jumped at the chance to use federal money designated for housing improvements to clear out the neighborhood.

Planners enlisted Methodist Town leaders like longtime resident Chester James, considered to be the “honorary Mayor” of Methodist Town, to help sell the idea of redevelopment to neighborhood residents. Promises of improved housing were made and residents, businesses, and churches were moved out.

Interstate highway system begins to reshape urban downtowns

But then reality set in. Residents complained of poor treatment by city staffers tasked with helping them relocate. Thriving businesses that were given money to open elsewhere discovered the money wasn’t enough to start again in a neighborhood where no one knew them. And when the time came for people to move back into Methodist Town, prior residents were not given first priority. Some 1,200 people were moved out of their longtime homes in a tight-knit neighborhood; less than half that number of different people were moved back into the newly built apartments.

Residents, including 91 year old Chester James, complained bitterly. James, whose own home was slated for demolition against his wishes, told City Council members “When that referendum passed, it passed with me voting for it. If I understood that you intended to take my home, I would never have voted for it. I have never, never, never, never wanted to get rid of it. We’ve got nice homes out here.” (St. Petersburg Times, May 20, 1975.)

The story behind Jamestown in the ‘Burg

His complaints fell on deaf ears.

The city ultimately destroyed the home of Chester James. But they renamed the neighborhood of Methodist Town in his honor. Thereafter, it would be known as Jamestown.

Sarah-Jane reminds me that all of this redevelopment wasn’t happening in a vacuum. The interstate highway system was concurrently reshaping vast segments of urban downtowns throughout the country, often in a way that disrupted historically African-American neighborhoods.

Sarah-Jane points out some of the questionable choices made while laying out the interstate and some of the small Black enclaves that were lost in the process. “In the 1970s the highways were laid in such a way that they got the cheapest land. Maybe. They laid I-175 right on top of Sugar Hill, which was the more affluent part of the Gas Plant neighborhood. So if we’re talking about the cheapest land, they could have moved it a few blocks north. But that’s not what they did.”

She also points out that the interstate severed the Gas Plant from the adjacent Campbell Park neighborhood, which had been almost one and the same previously. She notes: “The interstate severed those connections in the community and made it no longer viable the way it had been before, because Sugar Hill was no longer there. And all of those people, the businesses, the churches, the institutions, the social capital, was gone. The placement of the interstate was very destructive to the neighborhood and made it very easy to say – ‘look, it’s blight. We’re going to redevelop’.”

City declares the Gas Plant District as a redevelopment area

Our conversation has now led us to the Gas Plant.

In the late ‘70s, city leaders began talking about redeveloping the Gas Plant district in much the same way they had redeveloped Methodist Town. But this time, residents were wary. They had seen what had taken place in Methodist Town – promises made and then broken, and they were leery of something similar happening to them.

Their fears were justified. The City considered the Methodist Town redevelopment project a success story. When former Urban Redevelopment Director Anthony Caruso was asked in 1979 if the city had learned any lessons from the Methodist Town redevelopment, he responded “I don’t know that we necessarily learned any lessons. Our experiences in Jamestown were very good, given what we knew about the area, and what the city wanted to achieve.” (St. Petersburg Times, September 20, 1979.)

Broken promises to residents of the neighborhood

In 1978 City Council passed a resolution that the Gas Plant district was to be declared a “redevelopment area.” It was envisioned to support an industrial park and residential development. Jobs and homes. That is what the city said would come with redevelopment.

Millions of dollars were spent on the acquisition of land and demolition of the Gas Plant neighborhood. The money came from federal community redevelopment grants, designed to lift people out of poverty. Churches were to be relocated. Businesses would be given relocation money and advice. All in the name of jobs and homes for the area.

In her book Sarah-Jane notes that Gas Plant residents were promised, “in writing, that the neighborhood would be rebuilt with ‘new affordable housing and a modern-day industrial park.’ The plan also promised, in writing, 600 new jobs, with combined salaries of $5.6 million, by the end of the 1980s.”

Major League Baseball causes major complications

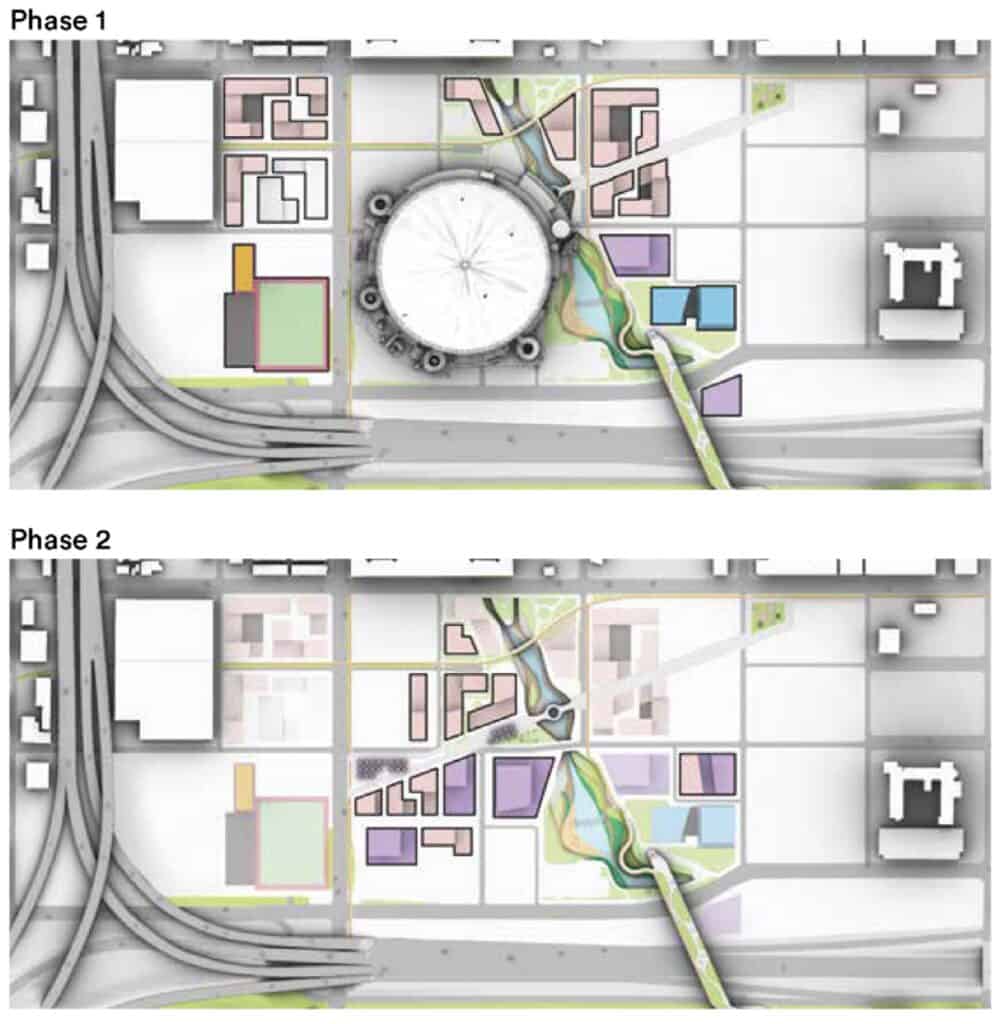

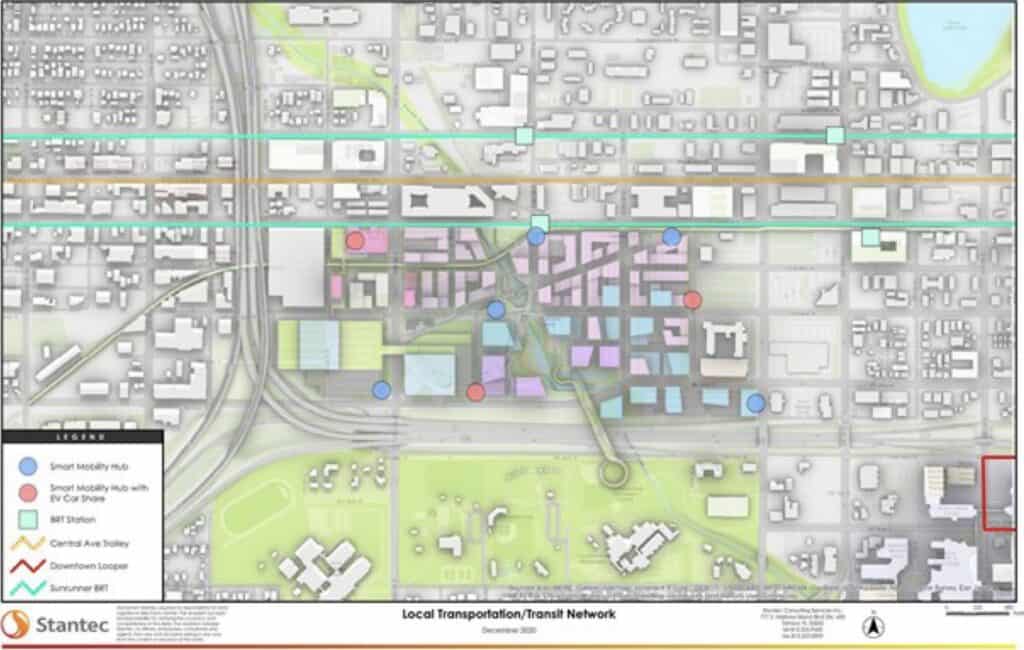

And then, in the early 80’s, talk shifted from industry and housing, to baseball. With an eye towards revitalizing downtown, city leaders now proposed building a stadium on the site of the former Gas Plant neighborhood, in the hopes of attracting a Major League baseball team. They believed that the tourist draw of sports would generate more dollars than jobs and housing could. Having already purchased and cleared much of the land, it was easier to convince the public that it was an appropriate site for such a venture, as opposed to the Gateway area or Al Lang Field, which were also mentioned as potential stadium sites.

Resistance was strong, particularly amongst former residents of the Gas Plant. City Council member David Welch (father of current Mayor Ken Welch), who represented the Gas Plant district, said in 1982, “When you went into this area and you moved out all the people, you said you were going to rehabilitate and create light industry and create jobs. You have a moral obligation to those individuals who were moved out for what you have told them.” (St. Petersburg Times, May 14, 1982.)

In a sign of just how complicated the topic is, Council member Welch eventually became a vocal proponent of the Stadium idea, and in 1986 City Council voted to move forward. Public debate shifted to whether it was fiscally wise to build a stadium. It was a highly risky and unproven strategy for attracting a team. Arguments raged, but not about the promises made to the former residents of the Gas Plant neighborhood. They had been largely forgotten. The promised jobs and homes had vanished.

As Sarah-Jane notes in Where Have All the Mangoes Gone, “While there is little evidence that, in the 1980s, the deliberate intent was to conclude the efforts begun in the 1930s, the goal was fulfilled.”

The Lightning were the first to call the stadium home

Completed as the Suncoast Dome in 1990, the Lightning hockey team was the first to call the new stadium home, playing three seasons there beginning in 1993. It would be nearly a decade before the Devil Rays debuted in 1998. While the team eventually enjoyed success, the stadium’s design was already considered outdated when it opened. It has never garnered positive reviews for fan experience, and the team’s attendance is perennially near the bottom of the league.

I asked Sarah-Jane about the reaction to the stadium from former residents of the Gas Plant neighborhood. She responded that “The narrative was that there was going to be redevelopment, and the city should be trusted to do it.” But ultimately, “It was another betrayal. It was another false, broken promise. And I think that’s the way a lot of people view it. Miss Daisy Swinton, told me that ‘That dome took my home.’ She lived across the street from where she worked. In that urban setting that we all want back, from the 1950s and 60s, where you could work and live in the same place.”

The loss of that tight-knit community still influences how people think of the Trop site. Sarah-Jane reflects: “For some people it’s a space and for others it’s a place. There’s so much meaning to the word place and the memories and the lived experience that goes there.”

——–

Rethinking the Trop Site in 2022

Now here we are, nearly 40 years later. Times have changed. Cultural sensitivity has grown. A former resident of the Gas Plant is now the Mayor of the City.

And people are learning about the history of the site. Stories have emerged thanks to groups like the Woodson Museum of African-American History and the African American Heritage Association who helped build a Heritage Trail in the historically African American community of the Deuces.

We now have three Black members on the City Council. And people like Sarah-Jane Vatelot have had their eyes opened to the wrongs of the past and are determined to do better in the future. She says “We’ve really lost something very important with losing the Gas Plant, so the challenge is – how do we bring something special back?”

I asked Sarah-Jane about what she felt the city’s responsibility was to the site’s history as we redevelop those 86 acres, and how that plays into the proposals for what ultimately is built there. She responded: “The city historically participated in the wrongs that were enacted – the economic suffering, the social/infrastructural violence, all of these things the city had a part in. So we need to think a little differently about it. Doing nothing and just saying ‘those people are gone now’ is not a solution.”

“We can’t come up with solutions until we understand the full story”

Sarah-Jane continues, “That just maintains the status quo and keeps things stagnant. Acknowledging what went wrong and trying to come up with solutions about how to do things better, how to be intentional about what we do there, rather than letting the market do it. Because if we let the forces of free market redevelop the site, what we are going to get is a bunch of luxury high rise buildings, right?”

“We know that. Being in St. Pete, we are seeing that happen. But the city actually owns this land, so they get to intervene, and they have that power to say we want things done differently here. So it’s going to have to be a collaborative effort through zoning regulations, through participation from city council, from ordinances, all of these elements have to come together, along with design, along with a willing partner developer, to say we’re going to include people in this redevelopment process.”

Creating an inclusive development in St. Pete

Sarah-Jane stresses the importance of sharing the history of the area: “We can’t come up with solutions that are relevant until we understand the full story. And we can’t understand the full story unless we talk about it and it becomes part of the public discourse.”

Sarah-Jane was invited to join the Sugar Hill development team, in large part, because of the painstaking research on the history of this area that she undertook while writing her Master’s Thesis. I asked her, if Sugar Hill ends up as the chosen developer, what efforts they would make in an effort to rectify past injustices.

She responded: “It’s a multifaceted approach. This has the opportunity to be the first time anybody has done anything like this at this scale – to create inclusive development. So what does that mean? That means access to attainable housing, not necessarily affordable, but attainable for all AMI brackets, meaning people who are 30 percent average median income, 60 percent, 90 percent, 120 percent. Currently the city’s definition for affordable housing is people that make 120 percent of average median income – that’s not affordable to a lot of people who live here.”

Mentor to the Mainstream Program

“So that’s a misnomer – affordable to whom? So, including attainable housing – attainable to more people on the site. Having people of all walks of life, making neighbors of people who wouldn’t normally be. We kind of set up a scene for people to live their lives.”

She continued: “We have to invest in workforce development, getting people who live in those areas ready to have jobs on the site. We’re not talking just construction jobs, it’s work at all levels. We have a “Mentor to the Main Stream” program, where the people who are working as part of the development team take on a mentorship role to bring people into the fold to train the architects and engineers of the future.”

She states that efforts must “include working on getting home ownership rates up in neighboring Campbell Park; decreasing the number of rentals in that area and getting people to own homes so that they can stay there. Working with the city to get property tax caps on those areas for a certain time so that they are able to start benefiting from the development, rather than being displaced by it. There are a lot of strategies such as setting up a community land trust in order to buy up properties and maintain them as affordable housing. We are exploring all of these new approaches that haven’t really been used at this scale, that are starting to emerge.”

Civic participation is essential for the development

Sarah-Jane stresses the importance of engagement: “Social participation and inclusion is a nod to what happened before, because people were excluded from the process, so including people in the process is an important step in righting that wrong.”

She goes on, “That’s how you make something belong, it’s a product of the people that made it and want to be a part of it, of their hard work. It will take all of us to make that happen, all of us to stay engaged, stay active, hold the developer accountable, hold the city accountable and make our voices heard as to what we want to see happen there. Who do we want living there? What kind of social capital can we build on that site? I think that’s the most exciting part. How do we get people involved in a meaningful way to make a meaningful difference in St. Petersburg?”

As I reflect on Sarah-Jane’s questions, I realize that we are a fundamentally different city than we were when the decisions were made about Methodist Town, the Gas Plant, and Tropicana Field. We now have a Strong Mayor form of government, and that Mayor grew up in the Gas Plant neighborhood. We have three African-American City Council members. This will not be a decision made exclusively by, and for, white people. But we also have thousands of new residents to the City who may not understand the depth of feeling associated with Tropicana and how the voices of the past still echo there.

Creating a space that respects and honors the past

And so, as a St. Pete resident looking at the Trop site from an historian’s perspective, I will add my voice to those who believe this is our opportunity to, in some way, make whole the neglected promises of the past. I believe the future of the Tropicana Field site matters. As does its future name. Sarah-Jane’s team is calling their proposed development Sugar Hill, after the most affluent section of the Gas Plant neighborhood.

It’s a name that was inspired by Sugar Hill in Harlem. Sarah-Jane tells me, “A lot of people in the south looked up to New York City as a beacon of freedom for African Americans, a freedom of artistic expression, and Sugar Hill was the home of poets and musicians and it was really sort of glamorized here in the south. That’s why we have Manhattan Casino, we have the Harlem Theater, we have all these references to New York as a place where people were free.”

Let us hope that whatever is built on the site of Tropicana Field, that it will be a place where people feel free. A place that respects and honors the past, and is welcoming to the entire community.

ADVERTISEMENT