This story is part of an ongoing series by local historian Monica Kile, highlighting the incredible and often unknown history of St. Pete.

As I grab a coffee at Craft Kafe, I’ve been watching the progress of the construction at the Art House St. Pete condominium at 235 First Avenue South. Seeing its name in the news recently got me thinking about the evolution of that postage-stamp sized piece of land.

Many of us recall it only as a parking lot, with a roundabout for the adjacent office building, 200 Central (which I still can’t help but call the Bank of America tower, but which was known as the Barnett Tower before that.) But what was there before it was a parking lot? Turns out, one of the most critical pieces of St. Pete’s history was once located there: the train station.

ADVERTISEMENT

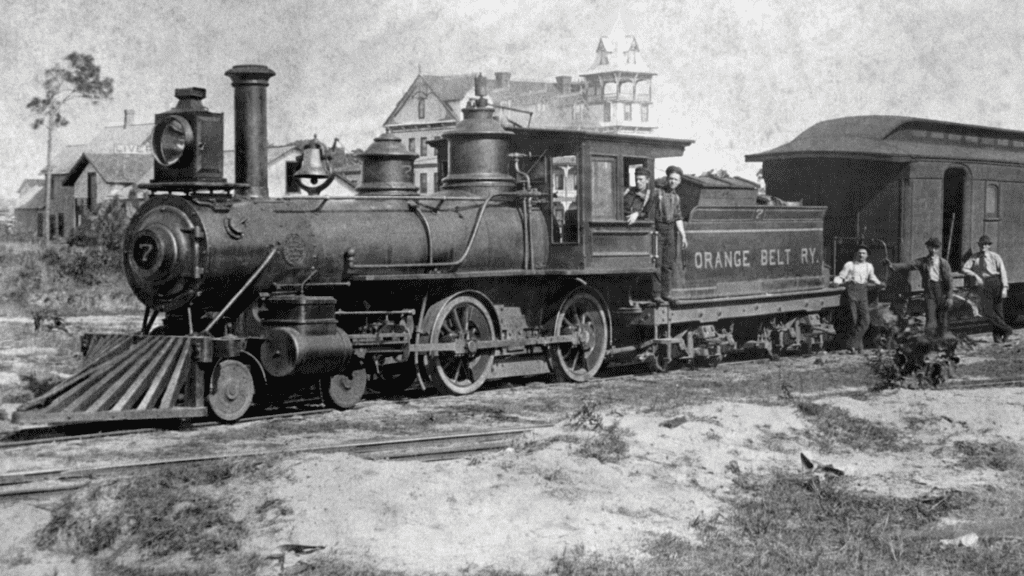

Trains were a pivotal part of St. Pete’s evolution. The city might not even exist if a Russian immigrant named Peter Demens hadn’t decided he wanted to bring a rail line to the Pinellas Peninsula in the late 1800s. His Orange Belt Railroad chugged into town in June of 1888, and a city was born.

Rail service led to St. Pete’s early boom

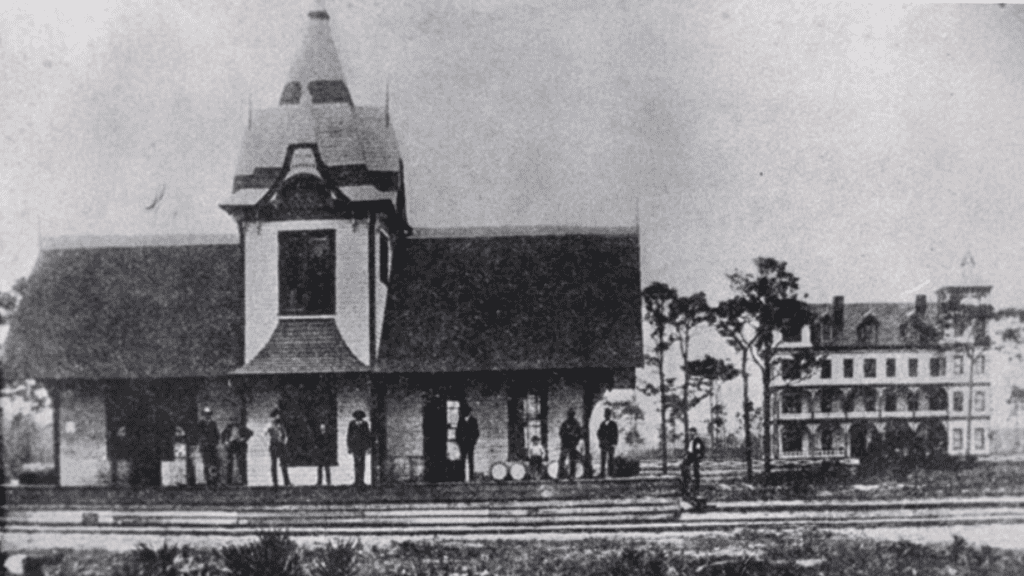

The first makeshift depot was located around Central Avenue and Ninth Street (learn more in this video), but within a few years Demens had built a Russian-styled passenger depot closer to the Bay, between Second and Third Streets, facing the railroad tracks on Railroad Avenue – today’s First Avenue South. Located behind the depot, across Central Avenue (originally called Sixth Avenue, as I talk about in this video) was the grand Detroit Hotel, which catered to the city’s earliest visitors.

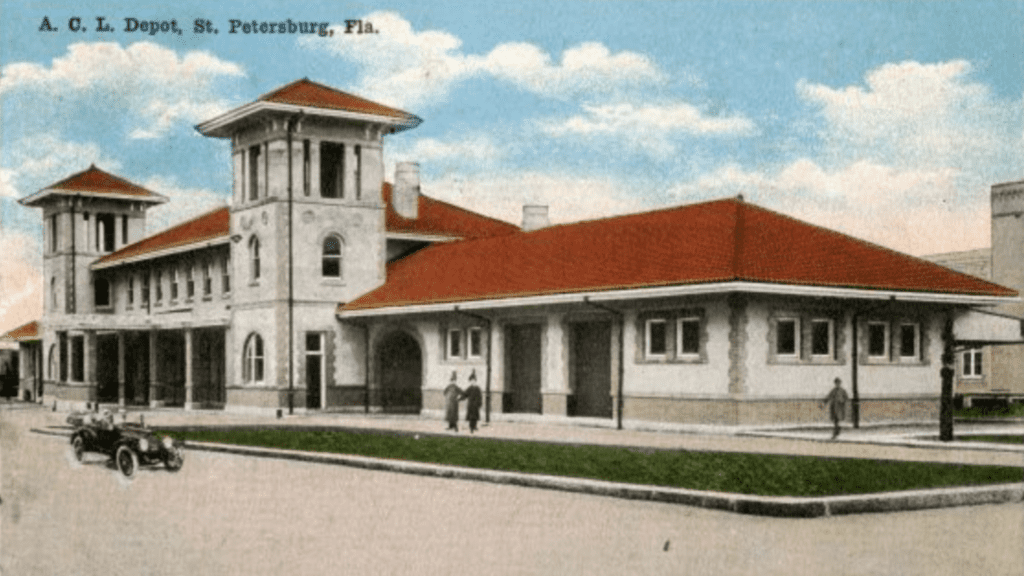

In 1895, the Orange Belt Railroad was taken over by Tampa railroad magnate Henry Plant, and by 1902, merged with the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad system. The ACL, as it was commonly known, built a new depot in the same location in 1906 and by 1915 had replaced that with a new $100,000 depot, one of the city’s earliest Mediterranean Revival style buildings in the city. Despite its popularity, or maybe because of it, citizens were soon clamoring for the station’s removal, citing the hassles and traffic jams that passing trains caused in the burgeoning automobile age.

When the editor of the St. Petersburg Times came out in favor of track removal, the argument gained momentum. As a concession, in 1935 the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad allowed sections of their right-of-way to be opened for motor traffic. The Depression and World War II distracted from the debate about removal of the downtown station and tracks, but by the early 1960s, the fate of the station was sealed.

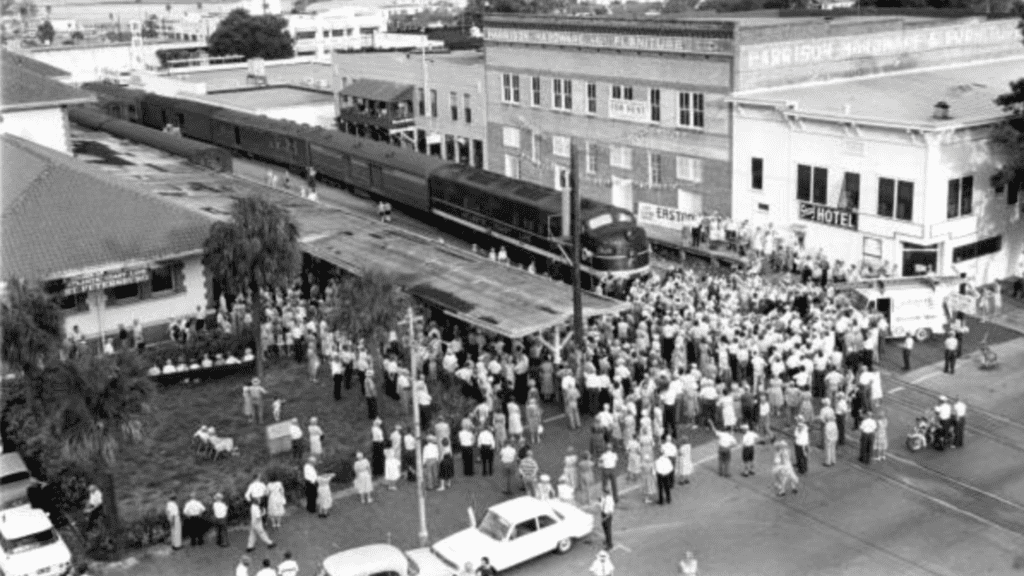

On June 2, 1963 a crowd of more than 1,000 people gathered to bid farewell to the final train to depart the downtown St. Petersburg train station. It was a raucous scene, with people pushing and shoving to get on board for the final voyage. Some 900 of them managed to climb aboard the train and ride it to its new station at 31st Street and 38th Avenue North. Overall, it was a celebratory day: Mayor Herman Goldner pulled up the first railroad spike as Miss St. Petersburg Diane Gregory looked on.

The beautiful Mediterranean Revival train station, once the pride of the city, closed almost 75 years to the day after the first Orange Belt Railroad chugged into downtown, marking the end of one era and the beginning of another. Unfortunately for downtown, the removal of the tracks confirmed that the age of the automobile was here to stay, a development with unintended consequences.

Trains gave way to the automobile generation

With the freedom to drive further from home and pack groceries and goods in the backs of their roomy new cars, St. Pete residents began spending their money at convenient new shopping centers away from the downtown core, and downtown business suffered.

After the departure of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad from downtown, the City ended up owning the southern portion of the block bounded by Central Avenue and First Avenue South and Second and Third Streets. In a sign of the times, they used it for parking. The northern portion of the block was occupied by various businesses that reflected the increasingly depressed nature of downtown.

Originally home to a hardware store, a grocer, a travel agency, a women’s clothing store, a sandwich shop, a real estate office, a cafeteria, and other retailers catering to tourists and downtown residents from the turn of the century, over time the block deteriorated and came to house pool halls and bars.

The owner of one of them, The Tarpon Bar, intentionally set fire to his business in 1982, causing a tremendous blaze that destroyed what was left of the block. He was arrested, convicted, and sentenced to ten years in prison.

From train to tower, St. Pete grows up

Various proposals for development of the block were put forth to the city in the mid 1980s, with the bid from Progress Florida for a 26-story office tower eventually winning out. The development, Barnett Tower, named for the major tenant, Barnett Bank, broke ground in 1987 and officially opened in 1990.

A portion of the western section of the block was used as a roundabout and surface parking. That is, until its recent sale to the Kolter Group for development of the luxury condominium, Art House. Groundbreaking took place in June of 2022. When completed, it will be the second tallest building in St. Petersburg, for a short while anyway.

The evolution of this fraction of a city block in downtown St. Petersburg mirrors the evolution of the city as a whole. From a small seaside village that welcomed the passenger depot of the upstart Orange Belt Railroad in 1888 to a city that tore down its train station in a nod to modern transportation choices in the 1960s, to a city struggling to find a new identity in the 1980s. St. Petersburg has become one of the coolest, most in-demand real estate markets in the country, with a cutting-edge arts scene, hip coffee houses, and vibrant restaurants.

The next time you grab a coffee at Craft Kafe on the ground floor of 200 Central Avenue, and find yourself marveling at the neighboring tower rising to the west, imagine yourself as a train passenger, 100 years ago, arriving in a booming, bustling city on the move. It’s not such a different picture than what you’d see today.

ADVERTISEMENT