By the early 1950s, Florida Power was the fastest growing of the 100 largest utilities in the country. Between 1960 and 1972, the average residential power usage by Florida Power customers more than doubled, due to a rapidly increasing population and the growing use of air conditioning. Florida Power would add 700 customers a week in 1971, and by the summer of 1972, 82 percent of those residential customers were using electric climate control.

The company continued to bring on new plants to build their generating capacity, including breaking ground on its first nuclear power plant at Crystal River in Citrus County in 1968. The timing was good, for while the demand for power was booming, the cost to create that power was about to skyrocket.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Oil Embargo

IIn October 1973, Arab members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) began to embargo the shipment of oil to the United States, Europe, and Japan, causing prices to skyrocket. At the time the embargo began, about 80 percent of Florida Power’s electricity was generated by oil. “We had all of our eggs in one fuel basket,” CEO Andy Hines said later. The cost of a barrel of residual oil rose 287 percent in just 18 months.

Inflation followed hard on the heels of the oil crisis that was rocking the nation. Suddenly the price of constructing the plants and other infrastructure needed to power Florida’s booming population were costing two and three times the initial estimates. The cost of wooden poles rose 153 percent in two years; the cost of copper substation fittings, 113 percent in one year.

Florida Power Leads on Environmental Change

Meanwhile, Florida Power was on the leading edge of a growing environmental movement. The company assumed a position of environmental stewardship and was recognized by the Environmental Protection Agency and local waste authorities for efforts to redirect and better process wastewater. These necessary changes, coupled with other newly enacted environmental regulations, further increased the cost of producing electricity. The era of consistently falling electricity rates was coming to an end.

Florida Power quickly began implementing strategies to help its consumers conserve energy and save money. Pre-embargo company efforts had promoted “all-electric living”. Now they reminded customers, “don’t forget to turn out all the lights.” Florida Power instituted what would become the largest “load management” system in the country, a program that allowed the company to turn off segments of power at any given moment to avoid brownouts and blackouts. Participating customers received a credit on their bill, and the program was highly successful.

A Changing Downtown

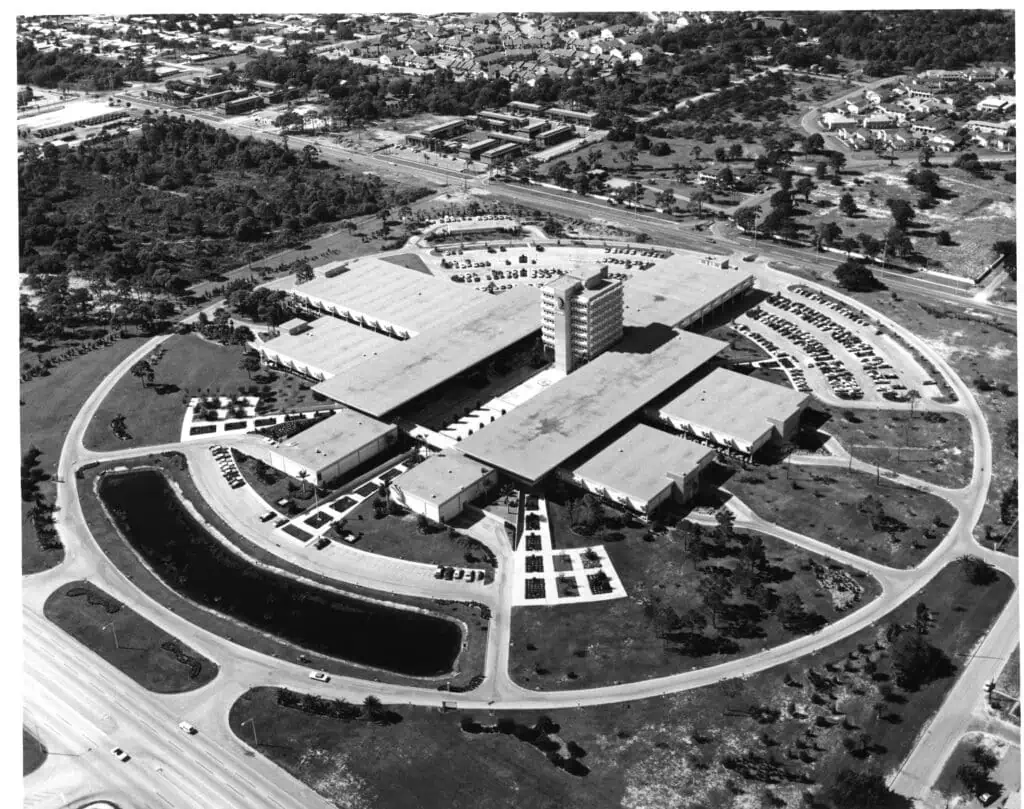

As Florida Power grew in the 1950s and 60s, they added additional offices scattered throughout downtown to accommodate their growing administrative staff. Other St. Petersburg corporations were starting a trend of moving their headquarters into the rapidly growing suburbs, where land was affordable and sprawling air-conditioned campuses could accommodate more employees, more comfortably. Hoping to stay downtown, Florida Power signed onto the ambitious Bayfront Plaza plan (not to be confused with the later effort known as Bay Plaza) to redevelop a chunk of the aging downtown core with a new office building and a convention hotel. In 1966 Florida Power pledged to lease the 15-story, 200,000 square foot high-rise office portion of Bayfront Plaza, but when the plan collapsed soon after, Florida Power announced it too would move out of downtown to a new 34-acre site on 34th Street, between 30th and 34th Avenues South.

34th Street South opened in 1972.

(which became Ceridian) and has recently just sold again.

The new location would put Florida Power’s headquarters, or General Office Complex as it became known, in close proximity to the suburban homes of many of its employees. The new campus would feature a 9-story, 250,000 square foot office for the executive and administrative personnel, with seven additional one-story buildings, each housing a different department, linked to the hub with sweeping canopies. Designed by prolific St. Pete architect C. Randolph Wedding (who later became Mayor) and project architect Peter Volmar, the planned building allowed for expansion of the facility to four times its original size. It would feature a cafeteria, running track, and in-house training school.

The Challenging 70s and 80s

The 1970s and 80s were a challenging time for both Florida Power and the City of St. Petersburg. The costs to create electricity were soaring, and downtown was dying. Talks of deregulation of the energy industry led most power companies in the country to begin diversifying their income streams, with many utilities starting new ventures in real estate and insurance industries. In 1982, Florida Power formed a holding company to facilitate diversification. The new company, Florida Progress, acquired interests in real estate, building products, aircraft leasing, and marina operations.

The state was continuing to grow, moving from the eighth most populous state in 1980 to the fourth most populous state in 1989. Florida Power signed on its one-millionth customer in 1986, but downtown St. Petersburg continued to struggle, losing popular retailers and businesses in droves. Recognizing the importance of helping to rejuvenate downtown St. Pete, Florida Progress renovated a historic hardware store on the corner of First Avenue South and Third Street, calling it McNulty Station. It was one of the first successful reinvestments in downtown in years, and inspired confidence that business might yet return to the city’s heart.

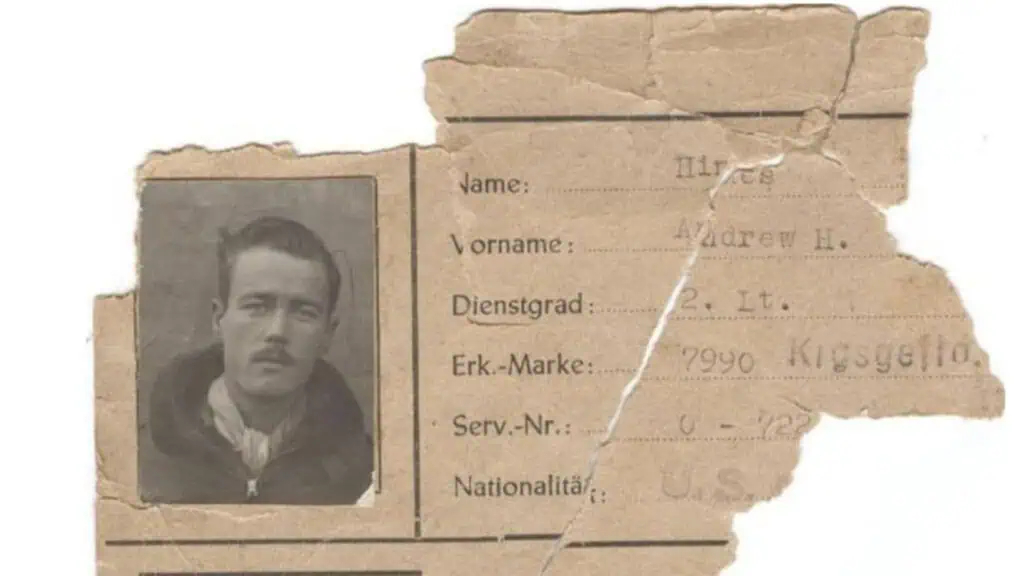

Florida Power would soon follow suit, led by CEO Andy Hines, a WWII veteran from Lake City, FL (who’d survived his time as a prisoner of war in World War II in part by keeping a hidden diary written on the back of cigarette packs wedged between a cover made from hammered sardine cans. Read the diary and learn more about Hine’s fascinating experience here.) With other cities courting the power giant, Hines felt strongly that the company should remain in St. Pete.

Back to Power and Back to Downtown

In the 1990s, after years of experience with diversification, Florida Power’s management decided that the business of power was power, and refocused on its core electric business, divesting itself of its real estate, insurance, and aircraft interests. Likewise, it returned to its roots in downtown St. Petersburg.

The large General Office Complex on 34th Street South, the picture of modernity when it was built in 1972, had become outdated and too big for the company’s needs (400 of the company’s 1,300 employees had moved to new business units in Orlando and Clearwater.) Meanwhile, downtown St. Petersburg had recently experienced another failed redevelopment plan, this one called Bay Plaza, which left the historic downtown core with demolished buildings, empty lots, and one nice new structure – the South Core building on the block between Central Avenue and First Avenue South and First and Second Streets. South Core featured a large parking garage, and thousands of square feet of space originally meant for a luxury retail store. Across the street was the new One Progress Plaza, the tallest building in St. Petersburg at 28 stories, with office space already being used by Florida Progress, the holding company of Florida Power.

A deal was struck to move the company headquarters back downtown, spread across three buildings: the South Core, One Progress Plaza, and, somewhat ironically—Bayboro Station, the power station built in 1924 at Bayboro Harbor.

for Western and Wildlife Art

“As a company, we’ve had a strong commitment to downtown,” said Joe Richardson, CEO of Florida Power in a 1997 article in the St. Petersburg Times. Indeed, the company’s show of faith in downtown St. Petersburg, from its original reinvestments through Florida Progress in the 1980s to the building of its new headquarters building in the late 1990s, would play a significant role in the renaissance of the city’s urban core.

Mergers and Acquisitions

The electric business was changing in Florida in the 1990s. New power companies entered the market, and those already here became more competitive. Florida Power executives realized that the company’s best move was to merge with Carolina Power and Light to form a new company, Progress Energy (playing off the name of Florida Power’s holding company, Florida Progress.) At the time, Florida Power was actually the bigger company, in terms of revenue and number of employees, but because Carolina Power and Light had the larger market capitalization rate, they became the “acquirer” in the deal. Company headquarters moved to North Carolina, with the state headquarters remaining in St. Petersburg.

In January of 2011, Progress Energy merged with Duke Energy, creating the largest electric utility in the country. In February of 2021, Melissa Seixas was named Duke Energy’s state President for Florida. Seixas started with Florida Power in 1986, working in the engineering department hand drawing the poles and wires of St. Petersburg – the same year the company began serving its one millionth customer. A true local, with degrees from Eckerd College and USF, she is deeply committed to St. Petersburg, as is Duke Energy. After all, the roots run deep here after serving the area for more than 125 years. We can only imagine that Frank Allston Davis would be proud of the role that the little power plant he built on the waterfront all those years ago has played in the city’s history.

Read Part One and Part Two of 125 years of Light and Power in St. Petersburg.

ADVERTISEMENT