If you’re interested in learning more about St. Pete from local historian Monica Kile, consider joining one of I Love the Burg’s walking history tours.

It’s beginning to feel a lot like 1950. The number of major real estate deals and development projects proposed in the past few months for the former Central Plaza area of St. Petersburg are reminiscent of the optimism and speculation that took place in that part of the city in the years following WWII.

What transpired 70 years ago was a story of hope and confidence, but also one of missed opportunities. The population growth and subsequent westward expansion of the city, encouraged by the suburbs, shopping centers, and road building of the 1950s, would turn out to be the death knell for downtown.

ADVERTISEMENT

Today, that tape is being rewound, with proposed new developments in the Central Plaza area offering to put new residents closer to downtown than they might otherwise be able to afford—aided and abetted by new public transportation and micro-mobility options. If you laid a target over the city of St. Petersburg, the bullseye would lay almost exactly on top of the location of Central Plaza, a name created to identify a specific shopping center, but which was later grafted onto the area at large.

Central Ave and 34th Street was once a gigantic pond

Before the shopping center was even a gleam in a developer’s eye, the crossroads of today’s Central Avenue and 34th Street (or Highway 19) was a rich, fertile, plot of muckland known as the Goose Pond. Stretching between Fifth Avenues North and South, and between 31st and 34th Street, the Goose Pond was decried as a swamp, a barren wasteland, and certainly a nuisance.

It was just as often lauded, as an important natural drainage site and an economic engine capable of producing abundant fruits and vegetables, with “watermelons so big a man could hardly carry them.” Its fertile soil was so rich with nutrients that it sometimes caught fire, but at such a low elevation that, during the rainy season, floods often made Central Avenue impassable through the Goose Pond.

This presented a particular problem as development moved westward in the city, and real estate salesmen were stymied when the streetcars couldn’t continue out to Pasadena and the beaches. Not to be deterred, the most ambitious of the developers, Walter Fuller, stationed rowboats at the edge of the Goose Pond to ferry prospective buyers to a waiting trolley on the other side.

For many years, the Goose Pond was utilized mainly by “truck farmers” that lived in other parts of the city and drove in to tend their land and carry out their produce by truck. A number of Japanese-American farmers worked the land at the Goose Pond, even persevering through World War II when suspicion was so strong that many of their tools were taken away for fear that they could be weaponized.

But as the city began to boom in the post-World War II years, and air-conditioning and DDT made Florida a more hospitable place to live, developers began speculatively building houses in as-yet undeveloped parts of the city. Downtown and most of its adjacent neighborhoods were developed in the 1910s and 1920s, and even some of the western neighborhoods on the shores of Boca Ciega Bay had blossomed by that time.

But when the boom went bust in 1926, building in the city ground to a halt, without the central part of St. Petersburg having seen much development. Not until after War War II ended would any serious development, residential or commercial, begin again in the Sunshine City. But when it did, it went gangbusters. During the decade of the 1950s, some 47,000 new houses were built in St. Petersburg.

Post-WWII boom saw a re-imagined St. Petersburg

During the post-war boom, not even low-lying, flooded swamp land proved to be an obstacle, with developers perfecting the concept of dredge-and-fill to create new land on which to build houses, much to the consternation of a budding environmental movement. The St. Petersburg Times led the criticism of “creating land from water” citing the damage to fisheries and sea-grass beds and the muddying of the once pristine Boca Ciega Bay as finger islands were created along the Pinellas coastline. Despite growing opposition and looming lawsuits, the practice of dredge-and-fill continued throughout the city, and developers’ sights were set on using it in the Goose Pond.

The impetus to fill the pond came in 1949 and 1950, when it was clear that the long dreamt of Highway 19, and the Sunshine Skyway Bridge were about to become a reality. With the new highway (which ultimately would run from Pennsylvania to Florida) set to be routed along 34th Street, and the bridge slated to connect the Pinellas peninsula to south Florida via Bradenton, the anticipated increase in traffic created a dream scenario for the construction of the newest fad in commercial development: the shopping center.

In 1951 a real estate syndicate, represented locally by Lowell Fyvolent, purchased four blocks along Central Avenue, between 34th and 31st Streets, and began plans to fill and level the land and recruit commercial tenants. Their investment was the tip of the spear in what would become a losing battle for downtown businesses.

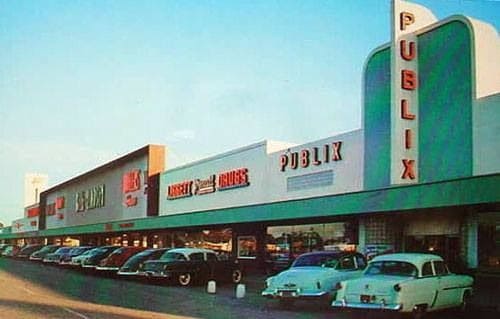

Even in 1952, we couldn’t get enough Publix

The newly named Central Plaza revealed the identities of its first tenants in 1952: Publix, A&P, McCrory’s, and Liggett’s Drugstore would offer goods and services to the recently arrived residents buying the thousands of new homes being built in the city (the decade of the 1950s remains the busiest home-building decade in St. Petersburg’s history.)

Developers originally planned for 750 parking spaces to accommodate all of their customers, but by the time Central Plaza opened in November of 1952, that had expanded to 2,500 parking spaces. Massive concrete lots stretched both in front of, and behind, the new shopping center, an amenity that was heavily advertised in the newspaper—a not-so-subtle commentary on the parking woes that shoppers experienced when visiting downtown merchants.

Those downtown merchants, including the famous Doc Webb of Webb’s City, the “World’s Most Unusual Drug Store”, did their best to counter the looming threat. Doc Webb even went so far as to protest the zoning that allowed for a shopping center to be built at all. Alas, it was a tide that would not be held back.

Somewhere between 30,000 and 50,000 customers visited Central Plaza on its opening day in November of 1952. A Wolfie’s Delicatessen, a popular Jewish deli that started in Miami, opened soon after. The influx of cars drew automobile-oriented businesses like Firestone and Rayco Upholstery (still in business today with their classic sign at 3121 Central Avenue.)

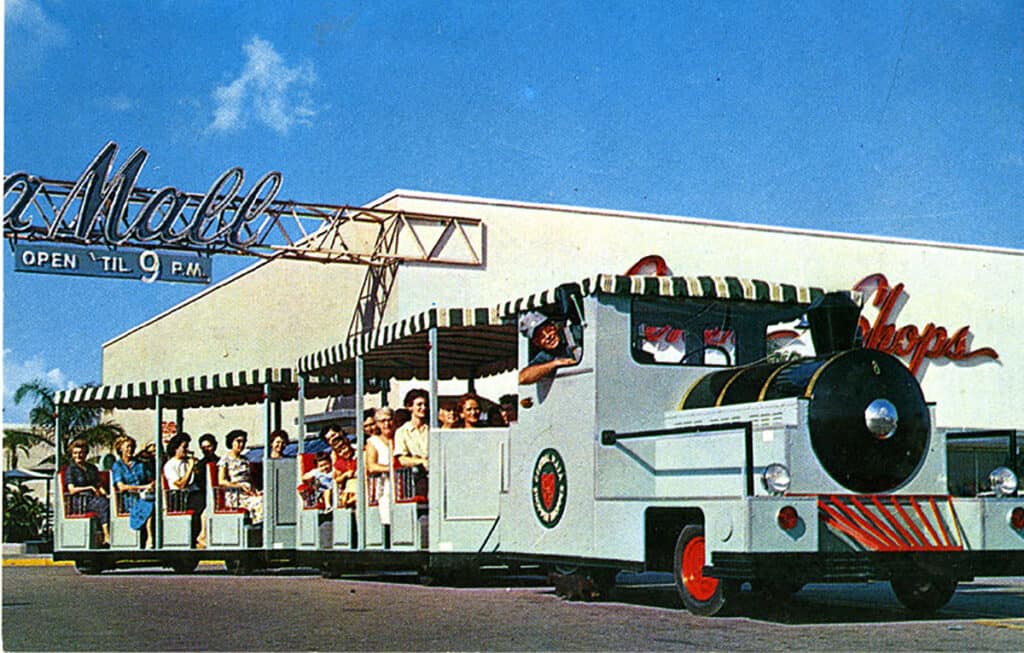

Business was so good at Central Plaza that the developers purchased several blocks across Central Avenue to create a “North Plaza”, which was renamed the Central Plaza Mall just before it opened in 1957. Designed by famous architect Morris Lapidus, (who designed the Fountainbleu and Eden Roc hotels in Miami, as well as Temple Beth El in St. Petersburg) the “mall” in this case was a covered pedestrian walkway between two buildings. (Those buildings, heavily remodeled in 2020 for the Octoplasma company, recently sold for $13.3 million dollars.)

While rapid development was taking place on either side of Central Avenue, a huge portion of the Goose Pond still remained undeveloped, resting in the hands of the Pinellas County School Board. The school board owned 55 acres of the Goose Pond, which they had purchased in the mid-1940s, intending to build a new high school to accommodate the city’s growing student population. When real estate values started to soar, they began flirting with developers eager to get their hands on the huge piece of land adjacent to the successful Central Plaza.

A major community debate ensued. Walter Fuller, a larger-than-life figure who had played many roles in St. Petersburg’s history – real estate developer, state legislator, historian, and, in the mid-1950s a member of the City’s planning board – argued that because the school board was a public organization, they had a moral obligation to see that the valuable tract of land was used for community purposes.

He was supported by the St. Petersburg Times, who lobbied for the school board to sell the land to the city for use as a central park or a civic auditorium. The Times vigorously argued that the school board was otherwise squandering a valuable opportunity to help the city engage in smart urban planning.

The arguments of Walter Fuller and the St. Petersburg Times were reminiscent of a much earlier proposal to turn the Goose Pond into a public park. That 1923 plan was created by John Nolen, one of history’s greatest city planners (now considered the father of New Urbanism) whose early designs for the City of St. Petersburg were voted down over concerns that they ignored the city’s strict racial segregation customs.

Like Nolen’s plans, the hopes for the remaining acres of Goose Pond land were also to go down in flames. In 1955, the School Board sold 50 of its 55 acres to private developers, and the remaining five acres to the United States Postal Service. They netted $802,000 in sales, a 1,400 percent return on their investment of $55,000 a decade earlier.

A post office opened at the corner of First Avenue North and 31st Street in 1957 and remains there today. A Montgomery Ward department store opened just west of the Post Office in 1959, on the land where the Walmart Supercenter sits today. Other developments evolved over the years, including the Plaza Fifth Avenue apartments, Morrison’s Cafeteria, and a Howard Johnson, among others. It was clear: any hope for the Goose Pond to remain a natural landscape, or even a community civic center, was gone for good.

Central Plaza to the next great American love affair – the mall

For many years Central Plaza remained an important shopping destination in the city, continuing to draw customers and even the businesses themselves, out of downtown. Many of the Central Plaza businesses, like McCrory’s and Lerner, had opened their first St. Pete stores downtown decades earlier and eventually closed them as their Central Plaza stores eclipsed their downtown sales.

In an ironic twist of fate, Central Plaza would soon be eclipsed by another trend in retail: the shopping mall. Tyrone Square Mall opened in 1972, and like Central Plaza had done to downtown two decades earlier, started a slow bleed of customers and businesses away from Central Plaza towards the air-conditioned mall.

By the 1980s many of the major stores in Central Plaza had closed. Montgomery Ward shut its doors in 1992. Discount retailers like Price Cutter and Family Dollar moved in. A Goodwill Store opened in the former Central Plaza Mall in 2008. The area began to develop a reputation as ragged and rundown, even downright dangerous.

Another transformational change would take place in 2001 when city leaders, including former Mayor Randy Wedding, whose family had owned land in the Goose Pond prior to Central Plaza’s arrival, helped move the YMCA of Greater St. Petersburg out of their grand, but dated, building in downtown St. Petersburg to the former location originally occupied by Central Plaza and its back parking lots. In 2002 PSTA opened the Grand Central Bus Terminal at 3180 Central Avenue, where the front parking lots of Central Plaza were once located.

Today, the area surrounding the crossroads of 34th Street and Central Avenue is again ripe for redevelopment. Some 40% of the acreage in the district is surface parking lot. It sits in both a community redevelopment area and a city opportunity zone, and its proximity to a booming downtown is catching the eye of developers once again.

The YMCA, which sits where the original 1952 Central Plaza shopping center once stood, recently announced plans to redevelop its 11.5-acre site, working with local developers Blake Investment Partners and Eastman Equity. Blake and Eastman also recently announced the purchase of the former Central Plaza Mall property just north of Central Avenue at 3365 Central Avenue. They propose a seven-story building for the location, featuring a mix of retail on the ground floor with apartments above.

The trajectory of that property in particular shows the wild swings in value of Central Plaza real estate. In 1947 the McCutcheon family, owners of a plant nursery in the Goose Pond, had purchased three blocks at that location for $6,000. They sold two blocks of it to the Central Plaza Mall developers in 1953 for $250,000, a roughly 4,000 percent increase in value (without even selling the entire original plot of land; they held on to the eastern portion of the property for several decades more.) When Central Plaza declined throughout the 1970s and 1980s, so did the land’s value. It sold in 1993 for $250,000, the same amount it had sold for 40 years earlier.

The property changed hands again several times throughout the 2000s with moderate increases in value each time. This latest sale represents a nearly 100% increase in value from the last transaction in 2014. All told, with numbers adjusted for inflation, the value of that land has increased about 16,000 percent since 1947. Not bad for useless swampland.

Central plaza to be revitalized once again

Other land in between the two developments that Blake/Eastman are working on has recently changed hands as well, with the shopping plaza immediately west of the Grand Central Bus Station selling in 2021 for $5.1 million. On the other side of the bus station, the Gallery 3100 apartments were recently completed, taking advantage of density bonuses for workforce housing, which allowed for 122 units rather than the base density allowance of 105 units.

It is likely that the YMCA project and the Blake/Eastman project at Central Plaza Mall will utilize similar bonuses, and all of the projects will probably receive tax benefits for being located in both an opportunity zone and a community redevelopment area.

Once again, the former Goose Pond/Central Plaza land is on the verge of transformational change. As downtown experiences a remarkable renaissance fueled in part by wealthy transplants from other states, a need for affordable housing for working locals has emerged. With increasing micro-mobility options like scooters and electric bikes, and its proximity to the new Sunrunner bus rapid transit line and the Grand Central Bus Station, residents of the developments in the former Central Plaza area will have easy access to downtown amenities and those of other neighborhoods along the Sunrunner line like Grand Central and the Edge District.

The promise and potential of the former Central Plaza area is exciting. Though the city has long since lost its chance to maintain the natural drainage and fertile land of the Goose Pond (and any park or civic amenity it could have become) perhaps these new developments can undo the major eye-sore of acres of parking lots created in the 1950s. Whatever the case may be, this next phase of development will continue a long history of growth and transformation for the part of town once known simply as the Goose Pond.

This article draws material from archival newspapers and secondary resources, most notably Jon Wilson’s meticulously researched book, The Golden Era in St. Petersburg: Postwar Prosperity in the Sunshine City.

What to read next:

- St. Pete history: A tale of two buildings – the YMCA

- St. Pete history: Art House rises where the last train departed

- The Don Cesar celebrates 95 years of incredible beachfront history

- History Half Hour – a Master Class all about the Sunshine City

ADVERTISEMENT